Defining dependency management

An IT system is developed by many teams and composed of different applications driven by the line of businesses and consumers. Applications need to interact to provide the overall system and interact through defined interfaces. Using well-defined interfaces allows the parts of the application to be worked on independently without necessarily requiring a change in other parts of the system. This application separation is visible and clear in a modern source code management (SCM) system, allowing clear identification of each of the applications. However, in most traditional library managers, the applications all share a set of common libraries, so it is much more difficult to create the isolation.

This page discusses ways to componentize mainframe applications so they can be separated and the boundaries made more easily visible.

Layout of dependencies of a mainframe application

From a runtime perspective in z/OS®, programs run either independently (batch programs) or online in a middleware (CICS®, IMS) runtime environment. Programs can use messaging resources like MQ queues or data persistence in the form of database tables, or files. Programs can also call other programs. In z/OS, called programs can either be statically bound or use dynamic linking. If a COBOL program is the first program in a run unit, that COBOL program is the main program. Otherwise, the COBOL program and all other COBOL programs in the run unit are subprograms1. The runtime environment involves various layers, including dependencies expressed between programs and resources or programs and subprograms.

There are multiple types of relationships to consider. The source files in the SCM produce the binaries that run on z/OS. To create the binaries, a set of source level dependencies must be understood. There is also a set of dependencies used during run time. These multiple levels of dependencies are defined in different ways, and in some cases not clearly defined at all. Understanding and finding the dependencies in source files is the first challenge.

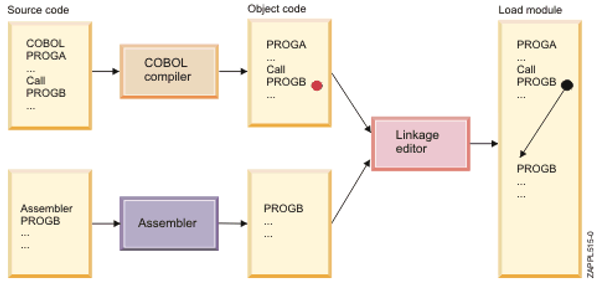

Building a program involves different steps:

- Compilation including any pre-compilation steps, defined as explicit steps or as option of the compiler, creates a non-executable binary (object deck) file.

- Link-edit, which assembles the object deck of the program with other objects and runtime libraries as appropriate. Link-edit can be driven by instructions (a link card) from the SCM or as dynamically defined in the build process.

These steps are summarized in the following diagram.

As part of the traditional build process, some additional steps, such as binds to databases, are sometimes included. The function of these steps is to prepare the runtime for a given execution environment. These should not be included in the build process itself, but should instead be included in the deployment process.

Source dependencies during the build differ from runtime dependencies

Most of the time when people think about an application, it is from a runtime point of view. Several components are required for an application to run. Some of these are required as dependencies, such as the database or middleware and its configuration, while others are required as related, such as other applications that might be called.

Everything running in a runtime environment starts as source from an SCM - or at least, this should be the goal when you consider infrastructure as code. Some source files represent definitions or are scripts that are not required to be built. Those that do require being built generally require other source files such as copybooks, but might not require the CICS definition, for example. Some of the source files are also included in many different programs - for example, a copybook can be used by many programs to represent the shared data structure. It is important to understand the relationships and dependencies between the source files, and when those relationships or dependencies have importance. The copybook is required to build the program, so it is required at compile time, but it is not used during run time. The configuration for a program such as the CICS transaction definition or the database schema is related to the application, but is required only for the runtime environment.

A concrete dependency is the interface description when calling a program. A copybook defines the data structure to pass parameters to a program. So, the copybook is important to be shared while the program is part of the implementation.

Programs call each other either dynamically or statically

On z/OS, there are two ways programs are generally called: dynamically and statically. Statically called programs are linked together at build time. These dependencies must be tracked as part of the build process to ensure they are correctly assembled. For dynamic calls, the two programs are totally separate. The programs are built and link-edited separately. At runtime, the subprogram is called based on the library concatenation.

Many organizations have been moving to increased usage of dynamic calls as that approach reduces the complexity at build time. However, this approach means that the runtime dependencies need to be tracked and understood if any changes are made that require updates in both program and subprogram.

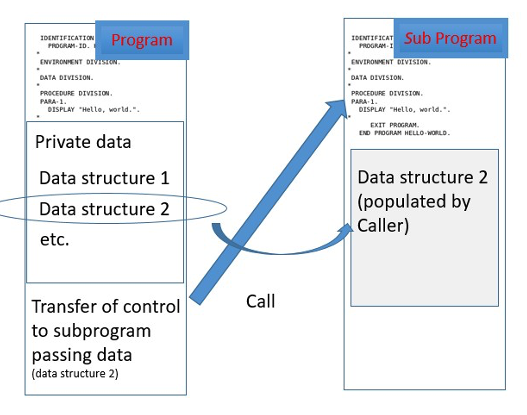

These programs and subprograms are interdependent even when using dynamic calls. When a program calls another program, generally they share data. A transfer of control occurs between the program and the subprogram with the main program passing a set of data to the subprogram and generally expecting some data in response.

Different mechanisms exist to share pieces of data based on the language or the runtime. However, there is a need for the caller and the called program to define the data structure to be shared. The call of a subprogram is based on a list of transfer parameters, represented in the interface description like an application programming interface (API), but it is more tightly coupled than today’s APIs that are based on representational state transfer (REST).

Commonly, shared data structure is defined in an included source file - for example, COBOL uses copybooks.

It is very common to define multiple copybooks for programs in order to isolate data structures and reuse them in other areas of an application component. Using copybooks allows more modularity at source level and facilitates dealing with private and shared data structures, or even private or shared functions.

Applications and programs

In a web application, it is relatively easy to define an application because the artifact that is deployed is the complete representation of such an application: the EAR or WAR file. In the Windows world, it is more complicated since an application can be made of several executables and DLLs, but these are generally packaged together in an installable application or defined by a package manager.

An application is generally defined by the function or functions it provides. Sometimes there is a strong mapping between the parts that are shipped, and sometimes it is a set of parts that run the application.

In the mainframe, we fall closer to the second case where applications are defined by functions. However, based on the way the applications have grown over the years, there may be no clear boundary as to where one application ends and another one begins. An application can be defined by a set of resources (load modules, DBRMs, definitions) that belong together as they contribute to the same purpose: the calculation of health insurance policies, customer account management, and so on.

At the source file level, the relevant files contributing to an application are derived from the runtime of an application. These files can usually be identified by different means: a set of naming conventions, the ownership, information stored in the SCM, etc. It may not seem obvious at first glance, but most of the time it is possible to define which source files contribute to a given application.

Scoping your source files to an application has many benefits. It formalizes the boundaries of the application, and therefore its interfaces; it allows you to define clear ownership; and it helps with the inventory of the portfolio of an organization. Planning of future features to implement should be more accurate based on this scoping.

Applications and application groups

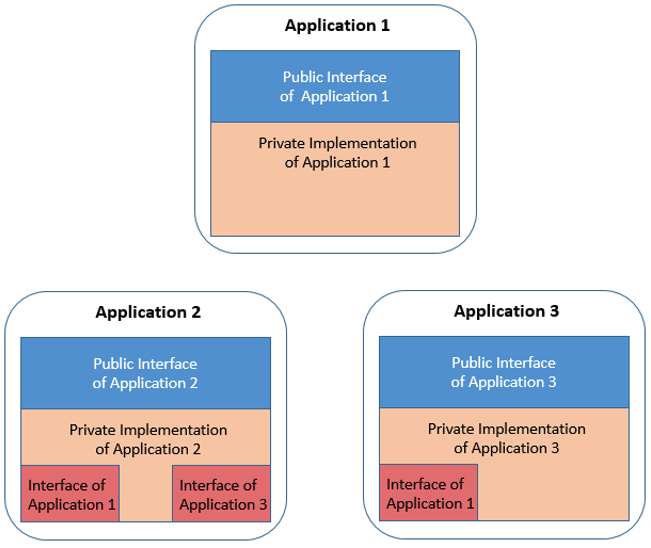

Within an organization, multiple applications generally make up the business function. An insurance company may have applications dedicated to health insurance, car insurance, personal health, or group health policies. These applications may be managed by different teams, but they must interact. Teams must define the interfaces or contracts between the applications. Today, many of these interactions are tightly coupled with only a shared interface defining the relationship.

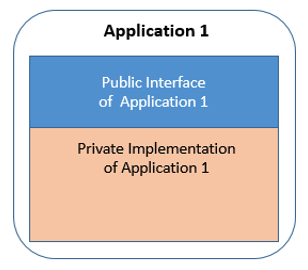

As we have seen so far, for traditional z/OS applications, the interface is not separate but defined in source via a shared interface definition, generally a copybook or include. This source must be included in each program build for them to be able to interact. With this information, an application can be defined by two main components: shared interfaces that are used to communicate with other programs and the actual implementation of the programs.

It is important to note that shared copybooks could be shared not only within an application, but also across programs or across applications. The only way other programs or applications can interact with the program is by including the shared interface definition. A z/OS load module does not work like a Java™ Archive (JAR) file, because it is does not expose interface definitions.

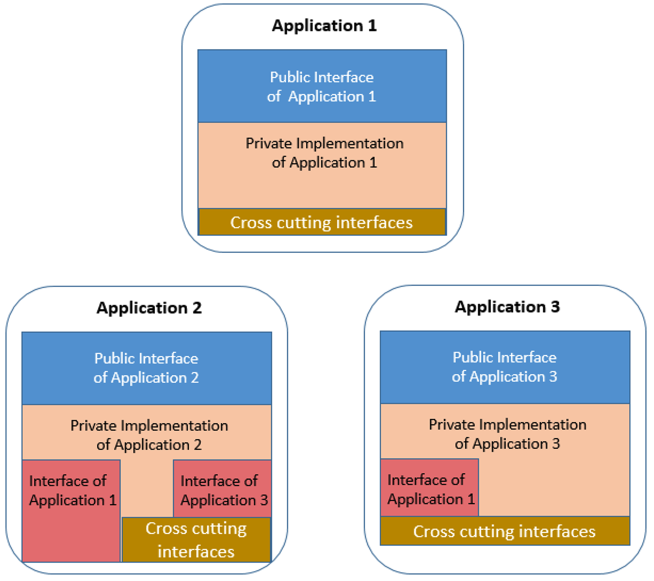

The following diagram illustrates the concept of an application having a private implementation (its inner workings, represented in tan), and a public interface to interact with other programs and applications (represented in blue).

As applications communicate, their implementation consumes the public interface of the applications with which they interact. This concept of a public interface is common in Java programs and the way the communication between applications is defined. This principle can also be applied to existing COBOL and PL/I programs to help explain the structure required for a modern SCM, and is illustrated in the following diagram, with the applications' usage of other applications' interfaces indicated in red.

Cross-cutting interfaces

There are additional capabilities that might need to be shared in addition to sets of data structures for application communication. These capabilities might include standard security or logging functions and can be considered cross-cutting, infrastructure-level interfaces (represented in brown in the following diagram). These capabilities may be developed once and then included in many different programs. It would be very helpful if these additional included capabilities could also be handled as shared components with their own application lifecycle. The challenge comes when these components change in a non-compatible way. These types of changes are generally infrequent but might be needed at times.

In the preceding sections, we have laid out some of the key factors when considering the source code of traditional mainframe applications. The environment generally consists of many different applications that can provide shared interfaces and could consume shared components, or cross-cutting interfaces.

The knowledge of these factors and their respective lifecycles can guide the desired structure of source files in the SCM. Several patterns are possible to provide appropriate isolation, but to also provide appropriate sharing based on different requirements.

Managing and life cycle of shared interfaces

As discussed in previous sections, applications often provide interfaces and rely on other applications' interfaces to communicate. Each application has its own life cycle of changes. In this process, changes are made. The changes are stabilized, and then go to production. In the end, there is a single production execution environment where all the applications will run. The applications must integrate, but the most common breaking point is their interfaces. If an application’s interface changes in a non-backward compatible manner and the other applications do not react to this change (to at least recompile the modules affected by the interface change), then the production application will break. Therefore, most changes are implemented in such a way so that the structure of the data that is shared is not changed, but instead filler fields are used, or data is added to the end where only applications who need to react to the change are required to respond. In discussing the management of shared interfaces, we will refer to the process of reacting to changes as "adoption", and the applications consuming the interface as "consumers".

The main types of changes that can be made to an interface are as follows:

- Backward compatible change: The interface changes, but the change is done such that all applications do not need to react. A typical example is when a field is added to a data structure, but this field does not have to be handled by most applications except a selected few, which requested this new field. Usually, fillers are used in a data structure and when people declare a new field, the overall structure of the data structure stays the same. Only the consumers interested in the new field need to adopt by using the new element in the interface. The others should use the new interface to stay current, but do not need to adopt it at this point. A standard practice is to adopt the change at least for those programs which are changing and recompiling for other reasons. Many organizations do not do this type of adoption until the change has made it to production, to be sure they will not be dependent on a change that gets pulled from the release late in the cycle.

- Breaking change: A data structure has changed in such a way that the overall memory layout of the data is impacted. It could be because of an array in a data structure. There are other cases, as well (such as changes in arrays or condition name changes also known as level 88). In these cases, all of the consumers need to rebuild, whether they have functional changes to their code or not.

Enterprises typically already have their own rules in place for how to manage cross-application dependencies and impacts. It is most common for shared interface modifications to be done in a backward-compatible manner, meaning a change of the interface does not break the communication. Or, if there would be a breaking change, the developers create a new copy rather than extending and breaking the existing interface. Thus, applications consuming that interface can continue to work even without adopting the new change. The only consumers that would need to rebuild would be those that will use the new feature (or other change that was made to the interface). This way of making backward-compatible changes depends on the developers’ expertise in implementing them.

Especially with breaking changes, a process needs to be defined for planning and delivering application interfaces' changes. Traditionally, the adoption process is often handled by an audit report generally run late in the cycle. However, having early notification and understanding of these changes helps improve and speed delivery of business function. Understanding your enterprise's current rules for managing shared interfaces is important for being able to accommodate them when implementing build rules in your new CI/CD pipeline system.

Adoption strategies for shared interfaces

Changes to public interfaces should be coordinated between the different applications. Various levels of coordination for the adoption process can be defined:

- No process (in other words, immediate adoption):

- In this case, the application owning the modified interface shares it by publishing it to a shared file system (for example, the COPYLIB). The next time applications consuming that interface compile, they will get impacted by the changes immediately. This is the unfortunate reality of many organizations today. Developers can be hit by unexpected changes that break their code. To minimize the risk, developers start to develop and test in isolation before sharing the updated interfaces. With Git and DBB, they can develop in isolation, build within their isolation, and fully test before they integrate with the rest of the team.

- Usually this scheme does not scale (that is, it works for small teams, or small sets of applications only) and slows down development teams as they grow. It can be applied for application internal interfaces without impacts to other applications.

- Adoption at a planned date:

- The application providing the shared interface announces (for example, via a meeting, email, or planning tool) that they will introduce a change at a given date, when the consuming applications can pick it up. This allows the consuming applications to prepare for the change, and is part of the resource planning. An outline of the future version might also be made available with the announcement.

- Adoption at own pace:

- The providing application publishes the new version of the interface to a shared location, which could be a file system, a separated Git repository, or an artifact repository. The teams using the interface can then determine themselves when to accept the change into their consuming application(s), or if they want to work with an older version of the interface.

Whichever adoption method is selected, we need to ensure there is only one production runtime environment. On the source code level, applications need to consolidate and reconcile development activities to ensure changes are not accidentally picked up before being ready to move forward. The most common method for achieving this is to use an agreed-upon Git branching strategy to organize and manage development work feeding into the CI/CD pipeline.

Pipeline build strategies for shared interfaces

When implementing rules for the build process in the CI/CD pipeline, different build strategies exist with different implications. There are two typical approaches you can consider:

- Automated build of all consumers: After changing and making a shared interface available to others, the build pipelines will automatically build the programs which include the copybook.

- Example: When a shared copybook gets modified and made available to others, the build pipeline will automatically build programs that include that copybook.

- Questions to consider with this approach:

- Who owns the testing efforts to validate that the program logic did not break?

- Who is responsible of packaging, staging and deploying the new executable? (This can only be the application owner.)

- Phased adoption of changed shared interfaces: If the modifications to the copybooks are backward-compatible, then consumers will incorporate the changes the next time they modify the programs. Thus, adoption of the external copybook change happens at different times.

- Since consumers of the shared interface are not forced to rebuild with this approach, this means that while some production load modules might run with the latest copybook, others might run with older versions of the copybook. In other words, there will be multiple versions of this shared interface included in the load modules in production. As long as the copybooks are modified in a backward compatible way, this should not be a problem.

The build strategy you pick for shared interfaces should depend on what your current workflow is, and if you want to continue with a similar workflow, or change that flow. General strategies for designing different builds with DBB and zAppBuild are described in Designing the build strategy.

For pipeline builds using DBB, zAppBuild's impactBuild capability can detect all changed files, such as modified copybooks or subroutines, and then based on that, it can find all the programs (in Git repositories) that are impacted by that change and build them. The most common use case for pipeline build automation with DBB is an automated impact build within an application (rather than between repositories). However, if you would like to force a rebuild of all consumers of a shared interface, including those in other repositories, then some considerations should be made to understand how the consumers include the external module, and subsequently, how to configure the build scope for external dependencies. Several scenarios for implementing specific build scopes depending on development practices and applications' requirements are described in the document Managing the build scope in IBM® DBB builds with IBM zAppBuild.

Resources

This page contains reformatted excerpts from Develop Mainframe Software with OpenSource Source code managers and IBM Dependency Based Build.

Footnotes

-

See the "Using subprograms" chapter of the Enterprise COBOL for z/OS documentation library programming guide. ↩