IBM Data Science - Best Practices

Distribution

As a general-purpose programming language, Python is designed to be used in many ways. You can build web sites or industrial robots or a game for your friends to play, and much more, all using the same core technology.

Python’s flexibility is why the first step in every Python project must be to think about the project’s audience and the corresponding environment where the project will run. It might seem strange to think about packaging before writing code, but this process does wonders for avoiding future headaches.

For a full guide on Packaging and Distribution in Python click here

Python Egg

Python eggs are a way of bundling additional information with a Python project, that allows the project’s dependencies to be checked and satisfied at runtime, as well as allowing projects to provide plugins for other projects. There are several binary formats that embody eggs, but the most common is ‘.egg’ zipfile format, because it’s a convenient one for distributing projects. All of the formats support including package-specific data, project-wide metadata, C extensions, and Python code.

Note that python Egg is being replaced by python Wheel as the standard for packaging python code

Python Wheel

So much of Python’s practical power comes from its ability to integrate with the software ecosystem, in particular libraries written in C, C++, Fortran, Rust, and other languages.

Not all developers have the right tools or experiences to build these components written in these compiled languages, so Python created the wheel, a package format designed to ship libraries with compiled artifacts. In fact, Python’s package installer, pip, always prefers wheels because installation is always faster, so even pure-Python packages work better with wheels.

Python and PyPI make it easy to upload both wheels and sdists together. Just follow the Packaging Python Projects tutorial.

Advantages of using wheels over eggs

- Faster installation for pure Python and native C extension packages.

- Avoids arbitrary code execution for installation. (Avoids setup.py)

- Installation of a C extension does not require a compiler on Linux, Windows or macOS.

- Allows better caching for testing and continuous integration.

- Creates .pyc files as part of installation to ensure they match the Python interpreter used.

- More consistent installs across platforms and machines.

Binary Repositories

Any developer knows that you must have a source code repository (e.g. Git) but then “why do I need a binary repository”?. Here is the short answer:

You manage what you code in Git, and what you build in Binary repositories (like Nexus).

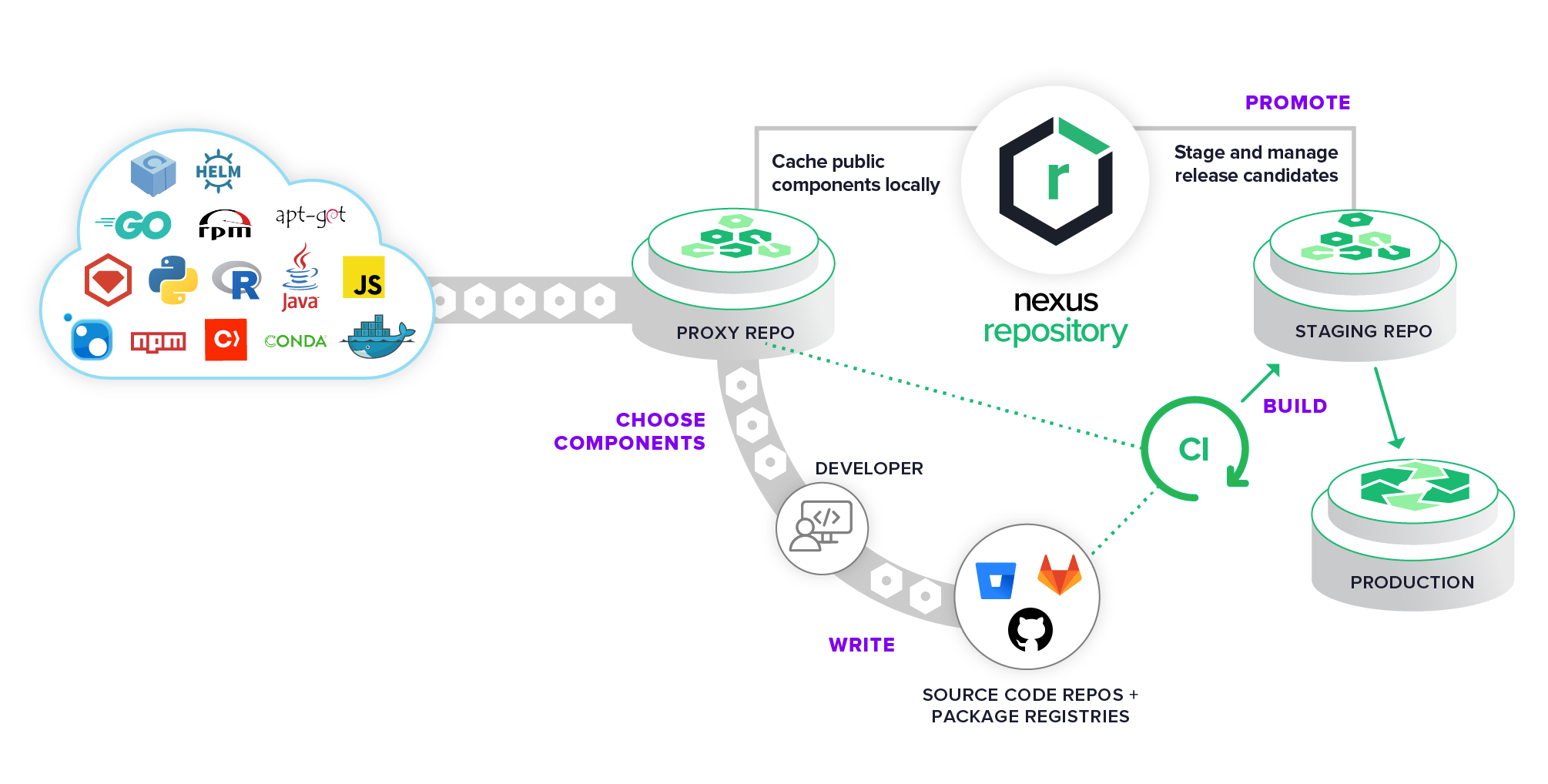

They can serve as a local copy, or “proxy,” repository for the language-specific package repositories/registries we discussed earlier. Creating these proxy repositories in a repository manager to store and cache your OSS components locally—rather than downloading them directly from an online repository every time you kick off a build—can provide some of the following benefits:

- Increasing build performance due to a wider distribution of software and locally available parts.

- Reducing network bandwidth and dependency on remote repositories.

- Insulation from outages in the internet, outages of public repositories (Maven Central, npm, etc.), or even removal of an open source component.

- Repository managers serve as a “single source of truth” for the binaries used in your build processes.

Lastly, another advantage is risk reduction in your build process. We alluded earlier to opening yourself up to certain risks when specifying the “latest” versions of a particular dependency, or even a version range, in your application-level package manager’s manifest. Downloading unvetted versions directly from online registries presents more risk because bad actors are increasingly poisoning the well, injecting malicious code into libraries or removing them all together.

Nexus OOS

Nexus OOS is an open source repository that supports many artifact formats, including Docker, Java™, and npm. With the Nexus tool integration, pipelines in your toolchain can publish and retrieve versioned apps and their dependencies by using central repositories that are accessible from other environments.

© Sonatype

Examples

To find examples for these guidelines, go to the example repository: MLOps pipeline.

In this implementation the model is distributed as Python wheel. After the model is documented trained and tested, it is packaged:

package.model: doc train test

pipenv run pipenv-setup sync

pipenv run pipenv-setup check

mkdir -p build

pipenv run python setup.py egg_info -e build bdist_wheel

The Python wheel therefore contains the model, which is saved as serialized object leveraging the joblib library:

def save_model(self, model: Any) -> None:

joblib.dump(model, self.model_file)

It also contains the model code, which is necessary to call the model via the classifier. Additionally the tumor data model is contained as a interface for sending input data to the model for prediction. This Python wheel is pushed to the Nexus repository, which is hosted on the Kubernetes cluster with a pre-defined container.

upload.model: version.model package.model

echo "[distutils]\nindex-servers =\n nexus\n[nexus]\nrepository: ${NEXUS_LOCAL_REPO_URL}\nusername: ${NEXUS_USERNAME}\npassword: ${NEXUS_PASSWORD}" > ./.pypirc

pipenv run twine upload --config-file .pypirc -r nexus ./dist/*

The script above uploads the specific version to a predefined Nexus repository. From there it can be accessed as any other Python package via pip install incl. the required version. The packaged model, makes it as easy as possible for the software engineer by using the classifier’s predict method without knowing the underlying details.